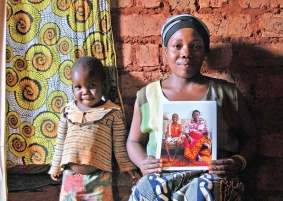

Jackie Niyonzima, 27, and her son Elias Vyizigiro, 5, pose with a picture of her oldest son and her mother who now live in Chattanooga. Money that Jackie’s mother sent back to Burundi helped build this small mud house.

Photo by Perla Trevizo /Chattanooga Times Free Press.

Inside a mud brick home in Burundi, five children sit in a circle on the reddish dirt floor and wait. In the center lies a tin plate filled with mashed manioc, a white root vegetable similar to sweet potato. Nine-year-old Bahati closes his eyes and bows his head to thank God for the food they are about to eat. His three younger siblings and a neighbor follow, but the longer he prays, the less they can contain themselves.

Finally, the prayer is over, and in seconds the mashed manioc is disappearing. Tiny arms crisscross to get handfuls. When it is all done, those still hungry scrape the pot with their fingers and lick the wooden spoon.

It is nearly noon and it is their first meal of the day. There might not be another until tomorrow.

Almost a whole continent and an ocean away in Chattanooga, Bahati's brother Erick Manirakiza looks forward to Wednesdays, when he gets a hot snack during his afterschool program.

On a recent afternoon it is two chicken strips. French fries. Baby carrots. Fruit salad.

This is his third meal of the day.

Erick sits at one of the long tables with his Styrofoam plate and black plastic fork to the side. Waiting patiently for his name to be called, he swings his black-and-neon-green Reebok Zig shoes back and forth. Those who are the quietest get to go first.

If Erick were back in Burundi, he would be leading the premeal prayer. Taking care of his four younger siblings. Holding a cup of water for his mother as she washes their faces outside their home. Fetching her when she has visitors.

After all, at 10 he is the eldest sibling, a full year older than Bahati.

But in 2007, Erick and his grandmother came here, the first arrivals in a wave of Burundian refugees still fleeing the ravages of a war that happened 40 years ago.

In a world of haves and have nots, Erick has become a have.

He attends Normal Park Museum Magnet School, watches "Wild Kratts" on PBS Kids on a flat-screen TV, listens to Justin Bieber, thinks crabs are "cool" and going to the beach is "awesome."

Far from Erick's life of possibility, Bahati's days are marked more by what he and his family don't have. Running water. Electricity. Health care.

Yet Bahati smiles. A lot, the same wide smile Erick has.

Veronica Niyibigira, grandmother to both boys, finds herself caught between here and there.

When people leave behind dirt floors and scarcity, bullets and blood, there is a sense that life must certainly elevate. In America, where there is high-speed Internet and access to education, life can only get better.

For some it does. For others, the complications of a new world can create longings for the primitive that can be hard to understand.

When Veronica came to America, she saw Erick take hold of a new start while the rest of her family remained behind. Sometimes her thoughts wander back to the place that she didn't want for Erick but that -- despite all its hardships -- still gives her comfort.

Erick doesn't remember much about Africa or the brother he left behind, except through pictures and stories Veronica tells him.

Yet Bahati thinks of Erick and his grandmother. And sometimes he cries.

Each is about to get a taste of the other's life.

A war and a woman

Veronica was born in Burundi, a hilly and mountainous country in East Central Africa, part of what is known as the Great Lakes region.

The landlocked nation is one of the world's poorest and most densely populated. Burundi is smaller than Maryland but has about 4 million more people. The nation has been besieged by violence since gaining its independence from Belgium in 1962.

Often called the first genocide of the Great Lakes region, the 1972 attacks against the primarily Hutu population by the Tutsi-dominated government killed some 200,000 Burundians and triggered the flight of 150,000 more, including Veronica.

When soldiers shot her parents to death, she fled to neighboring Tanzania. Her three brothers hid in a neighbor's home. Not until a decade later did she learn they had survived.

She doesn't know exactly how old she was when she left Burundi, only that she was in her teens.

Her documents say she's 43 now.

But it's hard for Burundian refugees to know their age. No records were kept.

During the conflict, neighbors turned on one another. People were hacked to death with machetes and burned alive. Women and children were gang raped.

Many women wrapped their babies around their backs and ran from the gunfire. Until they stopped running, they didn't realize their children had been struck and killed.

The massacres lasted only a few months but the violence forever changed the people who lived through it.

"The war was bad," Veronica said softly inside her Chattanooga apartment through an interpreter.

When asked about, it she seems to retreat inside her mind. When pressed, she lifts her skirt to show the scars from bullet wounds near her ankles suffered as she made her escape. Like many others fleeing for their lives, she hid during the day, ran during the night.

She drops down and starts crawling low to explain how she moved to avoid being seen. She gets up and mimics holding an assault rifle — "pop, pop, pop," she says.

Veronica's journey

Veronica lived in refugee camps in Tanzania for more than 30 years, where she had to use kerosene candles for light, walk long distances for drinkable water and wait for the rations of cornmeal, beans and oil the United Nations distributed every two weeks.

Her daughter, Jackie Niyonzima, was born inside the camp. So were Erick and Bahati.

When her daughter decided to follow Bahati's father back to Burundi in 2005, she left Erick behind with Veronica because he had been fathered by another man.

The desire for a better future for her grandson pushed Veronica to apply for resettlement, cut through her anxiety as she waited for an answer, propped her up when she questioned whether she had the strength to start over.

Veronica and Erick became the first of about 80 Burundian refugees who would move to Chattanooga over the next several years, part of a group of 8,000 "1972 Burundians" accepted for resettlement in the United States.

She spoke only Kirundi and, like 80 percent of the Burundian refugees considered for resettlement, didn't know how to read or write.

Yet she set out anyway, not knowing what lay ahead, much as she had when she fled Burundi.

They arrived in Chattanooga on July 3, 2007, a day before their new country celebrated its independence and the beginning of their own long journey to freedom.

But after more than 48 hours of travel, as she and Erick were swept along from airport to airport, blinded by bright lights and startled by disembodied announcements in languages she couldn't understand, her resolve gave way to fear.

Bazungu -- pale-skinned people -- greeted her and Erick at the Chattanooga airport and whisked them off to the mission home of a Hixson church. White women led her by the hand, showing her what to do with things she had never seen before. A stove. Microwave. A table lamp.

A rising panic gripped her and that first night she was unable to stay inside the house. She felt that everyone was out to get her. In her mind, she couldn't trust anyone.

She had just spent decades in isolation in a camp, not being part of Tanzania, not being part of Burundi. She had learned to fend for herself and to assume everyone else would do the same.

So she stayed outside, she said, while Erick slept inside the house.

The following day was the Fourth of July.

Because of her uneasiness, she and Erick were moved to a volunteer's home in St. Elmo, where a celebratory Burundian recipe found on the Internet was prepared for them.

Erick was in a guest bedroom, sound asleep. But Veronica couldn't bear to even go inside the house.

Meanwhile, fireworks boomed, lighting the sky as children shouted with joy. But all Veronica could hear was the "pop, pop, pop" getting closer; the nightmare sounds had followed her to America.

She ran.

In her panic, she left Erick behind.

In with the new

She didn't know where she was going, but she had to get away.

First she kept to the street and sidewalk, and she was quickly accompanied by church volunteers driving alongside.

For four hours they tried reasoning with her, in English and in French. Finally a neighbor who spoke Swahili, the language spoken in Tanzania, was called to help and convinced her to stop.

That same evening, Veronica and Erick were taken to another volunteer's home in the Chattanooga Valley across the state line in Georgia where she would spend the night. The volunteer had accompanied Veronica during her first night in Chattanooga. Maybe Veronica would feel more comfortable with her.

But Veronica ran again, this time with Erick tied to her back. She hid in the woods. When the sun went down, she unwrapped a piece of cloth from her waist for little Erick to sleep on.

She doesn't remember much of what happened that night, only that police found them the following morning. A missing persons report had been filed.

But even after she returned to the mission home in Hixson, she was hesitant, unsure of people's intentions. It wasn't until other Burundian families arrived a few days later that she began to relax.

She started to believe her old life was over, to smile and laugh.

But the new life wouldn't be easy, at least not for her.

From cannot to can do

Erick seemed to be sold on his new home from the beginning.

The boy whose African name — Manirakiza — means "God's grace" played right there in the airport with his new soccer ball and small yellow toy truck. They were gifts from volunteers who greeted him and Veronica, and his first real toys.

After five years in Chattanooga, he is no longer the refugee boy who grew up without electricity; he's the fourth-grader who wants to be a soccer player, then retire to be a scientist.

Erick likes math and science. He gets As and Bs in school and his teachers believe he can grow up to be anything he wants.

He calls Veronica "mom" and speaks to her in Kirundi. To everyone else, he speaks English.

He has more friends in America than in Africa, he says. He also notes that he doesn't like to run barefoot anymore. In Africa, thorns got inside the soles of his feet all the time and he had to dig them out.

"I'm used to wearing shoes now," he says.

In Tanzania, Veronica was the family matriarch. She knew how to survive, live off the land, make do with very little.

Here, she was a single mother without job skills, education or even the ability to tell time.

At the beginning, volunteers drew a round clock on a piece of white construction paper for her with the hands pointing at the digits to show her when she had to walk Erick to school.

Because she had difficulty adjusting to a work schedule and the environment, she spent several years unemployed.

Slowly, things are changing, though the old ways may always come alongside the new.

In her North Shore apartment, Veronica takes a frozen fish out of the refrigerator. The fish, a little over 12 inches long, looks enormous in her hands.

She moves swiftly from the kitchen to the adjacent living room, where she plops the fish on the coffee table.

Raising a cleaver, she chops the fish in half.

She cuts slits on the fish and rubs it with salt, just like she did back in Africa. But instead of fetching wood for the fire, she turns on the electric stove, pours oil in a pan and drops half of the fish into it.

There's no denying that the changes have been enormous.

Five years ago, she had never seen a light switch. Now she has a cellphone.

She shops at Walmart. Does laundry in a washing machine. Watches DVDs of Burundian and Congolese singers.

One of her first cellphone bills was more than $1,000 because she didn't realize that a call to Burundi can cost several dollars per minute. And she makes a monthly payment toward a $900 ambulance bill stemming from a 911 call she made.

But she has the support of two communities.

Fellow Burundians looked over her shoulder when she registered Erick at school and told her the letters of her name in Kirundi so she could write them slowly one by one, V-E-R-O-N-I-C-A.

And she has her church community, the members of East Ridge Presbyterian Church who have become her friends.

One recent Sunday after the service, one of them sat with Veronica in a pew to pay her bills. First the electric bill, then her cellphone. Veronica just wrote her name on the bottom.

She has a job now. She works deboning chickens by hand at Pilgrim's Pride, earning about $10 an hour.

She is unable to bring any of her other relatives to this country because U.S. law requires that she become a citizen first, and she can't do that until her English gets better. But like many of the Burundian refugees here, she sends money back home.

Before leaving for work from her apartment, she will change into two sets of sweatpants. Put on her green fleece and brown corduroy jacket. It's always cold inside the chicken plant.

Her hands will tire from deboning hundreds of chickens. Her feet will ache from standing for hours at a time. Her heart will sink because there's no one to talk to, no one who speaks her language. Sometimes she thinks of Burundi.

The pictures in her mind have dimmed with time. But a story that words cannot tell will soon be on its way.

Burundi today

It is a two-day plane trip to Burundi's capital city of Bujumbura and a two-hour car ride to the village of Nyanza-Lac for a reporter to even get near the family that Veronica and Erick left behind.

Off the main road, narrow dirt roads that look more like hiking trails lead to a small mud house where the rest of the family lives.

Veronica's Chattanooga-earned money helped build the house. It has four small rooms divided by an space in the middle where they cook and eat.

Jackie Niyonzima, 27, makes a living farming. It's a seasonal job and, even when she works, she makes barely $30 a month.

For food, Jackie grows manioc in front of the house. The fresh roots can be cooked much like potatoes and the leaves like spinach. When she has money, she buys a couple of pounds of beans for about $1 and spends $2 a month for the kerosene candle.

There's no meat, no milk.

Jackie didn't know when she left the Tanzania refugee camp that her mother and son would be resettled in the United States. If she had stayed, she, too, could have applied for resettlement and possibly come to the United States.

She says she regretted leaving them from the first day she arrived in Nyanza-Lac, the small town that many of the refugees have returned to and one of the places where the violence started.

Her son Bahati, which means "lucky" in Kirundi, runs barefoot. He plays with balls made with plastic bags wrapped together tightly and toy cars made out of cardboard -- just like Erick did when he lived in Africa.

Bahati might get to finish elementary school, which is free. If his mother can't afford the estimated $50 a year to continue his education, Bahati will probably live off the land, like 90 percent of the population in Burundi does.

A reporter brought out photos of Veronica and Erick taken this summer in Chattanooga.

Jackie gasped and smiled when she saw them. It was her first glimpse of Veronica and Erick in seven years. Veronica and Jackie talk on the phone often, but her daughter hadn't seen pictures of them.

In one, Veronica stood on the front porch of a house wearing blue jeans and a polo shirt, ready for work. In Burundi, women never wear pants.

Jackie kept looking at the pictures, leaning her head against the shoulders of friends and relatives as they all stared at a grinning Erick and a plumpish Veronica sitting on a brown sofa inside their North Shore apartment. In Burundi, only the well-off are plump.

Bahati, too, held on to the pictures.

The future

Photos went to Burundi, and photos returned.

Erick was glad to see images of his mother and his siblings. Some of them he has never even met.

"But it made my mom really happy," he said of Veronica.

As he flipped through the pictures he kept saying "Oh my God!" closing his eyes and laughing, asking to see more.

There is a chance Erick could bring his brother to America, but it likely would take decades. First, Erick must turn 21 before he can legally file Bahati's sponsorship application. Because he is a sibling, immigration law assigns him a lower preference than if he were a parent or child. If he filed today, he would face an 11-year backlog.

But when Erick is old enough, will he remember? Will he try?

During a recent science lab class at Normal Park, he learned about Benjamin Franklin and his inventions.

On the table, a small book "The Shocking Story of Electricity," sat on top, next to the PVC pipes, wool clothes and balloons for an experiment on static electricity.

"Watch out! Watch out!" Erick told classmates as he chased an orange balloon that rolled off the table.

Franklin, his teacher told the class, had to work for his older brother.

"How many of you have a brother?" she asked.

Erick raised his hand.

By Perla Trevizo

Source: timesfreepress.com