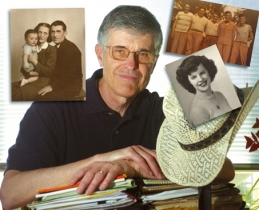

IllustrationThe Internet and DNA tests were useful tools for Richard Hill in his search for his past. In the historic photos, top left, baby Richard poses with his adoptive parents, Thelma and Harold Hill; top right, his birth father, Douglas Richards, center, poses with his four brothers; bottom right, his birth mother, Jackie Hartzell, died in an accident a year after he was born.

ROCKFORD -- For 26 years, through a series of false leads and fabricated records, Richard Hill repeatedly was frustrated in searching for his birth father.

Frustrated, but not deterred.

When he began, the tools he would need to complete the search had not yet been developed. Aside from his own persistence and resourcefulness, it was the rise of the Internet and DNA testing that solved the mystery.

Hill, of Rockford, has become an advocate for using those high-tech tools, and he has set up a Web site, www.dna-testing-advisor.com, to help other adoptees seeking information about their biological past.

"Here DNA had solved the problem for me after 26 years," he said. "I'm thinking there are a lot of adoptees out there who don't know anything about this."

Until he was 18, Hill, now 63, did not know he was adopted. It was the family doctor who let it slip. Hill was surprised but too focused on starting college to think much about it, let alone start searching for his birth parents.

Besides, when he was born in 1946, out-of-wedlock births were taboo and open adoptions decades away. On his deathbed in 1978, Hill's father told his then-32-year-old son, "You must know by now you were adopted."

Richard's birth mother, his father told him, was "a cute little Irish girl" named Jackie from the Detroit area who was unwed at the time. Harold and Thelma Hill, unable to have children, had heard about her through friends, and she came to live with them during her pregnancy. They took her to the hospital in Lansing, where he was born, paid the bill and kept Richard to raise as their only child.

A year or so later, Jackie died in an auto accident.

And one more thing, his father said: Jackie had another son from an earlier marriage, Richard's half brother. "I think you should find your brother," his father said.

A few years later, Hill joined a support group for adoptees and met a volunteer who helped find out more about his birth mother. Her name was Jackie Hartzell, and she and her sister died when a Jeep they were riding in rolled over near Northville, he learned.

"My mother was already dead, so I never got to have that reunion," he said. "But the fact I had a brother, that's what kept me going, to try to find him. When you grow up as an only child, you're sometimes jealous of those who have brothers or sisters."

With the volunteer's help, he found his half-brother, who until then did not know about Richard. They have become close.

Finding relatives on his father's side would be more difficult. Hill didn't know it at the start of his search, but two facts about men would help him: The Y chromosome passes from father to son, and, in American culture, so does the surname.

He knew nothing of his birth father. He tracked down friends and relatives of his birth mother, but none knew his father's name. One birth certificate listed his adoptive parents as his birth parents. Another listed Jackie Hartzell's ex-husband as his father, but Hill considered that unlikely.

False lead

He obtained adoption records listing his birth father only as an unnamed Polish man. The same volunteer who had helped find his half-brother got a judge's permission allowing her to see the closed adoption file.

In those records, she found Hill's birth mother had named a man with a Polish surname as his father. The volunteer arranged for them to meet in early 1990.

"I thought I was talking to my father," Hill recalled. And the man sitting across from him was thrilled he might be talking with his son, but he also was a little skeptical. He had been married three times, the man said, and never had been able to father a child. Just to be sure, Hill suggested they undergo a DNA paternity test. The results showed they were not related.

"I think that was the most deflating moment for me," Hill said. "I had been chasing this Polish man all these years. He would finally have a son. I would finally know who my father was. We were both disappointed."

He was at an impasse, but time and emerging technology were on his side. In 2006, he learned of a new DNA test more commonly used by genealogists than adoptees to find their ancestral links.

Through an online service called FamilyTreeDNA, he ordered a Y-DNA test, comparing his genetic makeup with that of other men in the service's database. Those he mostly closely matched likely shared a common ancestor, and, he believed, probably had the same surname as his birth father.

"It was kind of a crazy idea," he said, "but I thought this could work."

His closest match, the test showed, was a man in Florida with the last name of Richards. He e-mailed the man and asked if he had relatives in Michigan. The answer was, "No."

Hill turned back to his growing pile of records. He pulled out a copy of his mother's Social Security work record he had ordered 16 years earlier. It showed she had worked at a bar called Dann's Tavern in Livonia in 1945. The bar owner's name was Douglas S. Richards.

"Bingo," he said. His wife sat across from him in their lakeside home. "I think I just found my father," he told her. But where was he, and was he still living?

Through records in Livonia, he learned Dann's Tavern was long gone, and Douglas S. Richards had moved to Texas. He died there in the mid-1980s, Hill learned. On the Web site Ancestry.com, he searched Social Security death records for a Douglas S. Richards who died in Texas in the mid-1980s. He found one.

From the library in the town where Douglas Richards had died he obtained an obituary identifying him as a rancher who once lived in Michigan. He tracked down a Richards relative who confirmed Douglas Richards had owned a bar in Livonia. He was one of five brothers, all of whom had been in the Livonia area in 1945. Any one of them could have been his father.

Another test

All five brothers were dead, so testing their DNA was out of the question. Hill turned back to the Internet and learned of one more DNA test -- a "sibling DNA test." All five Richards brothers had sons. Hill wrote them, and they all agreed to submit a cheek swab for testing.

The one most closely matching his DNA would be his half brother, Hill believed, and the other four would be his cousins. The tests showed Douglas Richards Jr. was his closest match, his half brother. Douglas Richards Sr. was his father.

Since then, Hill has concluded he likely was conceived around Aug. 14, 1945, V-J Day, a time of celebration and drinking marking the Japanese surrender and the end of World War II. His birth mother, he believes, deliberately listed a wrong name for his birth father, because his actual father was married.

In July 2007, he attended a Richards family reunion near Houghton Lake. He learned more about his birth father, a "serial entrepreneur," who had started or been involved in some 40 businesses. His one memento is a cowboy hat his birth father wore on his Texas ranch.

In October 2007, Hill and his wife, Pat, took a two-week tour of the South, meeting other Richards relatives. In addition to his maternal and paternal half brothers, he has a paternal half sister born three months after him.

"Some people have said to me, 'Oh, you've found your real parents,'" Hill said. "I'm very sensitive to that. I correct them. I say, 'My real parents are the people who raised me. I found my biological parents.'

"I don't have to give up anybody in my adopted family. It's not an either-or thing. You're just adding on. You can't have too much family."

By Pat Shellenbarger

Source: mlive.com