A US military doctor is planning to return to a North Vietnamese soldier his arm he had amputated almost half a century ago.

Dr. Sam Axelrad has been keeping the unique “souvenir” after saving the Viet Cong soldier’s life in 1966.

“This is a miracle,” he said last week being told that the owner of the bones had been traced.

A day after Thanh Nien published a story about the American doctor and his quest, a reader called the newspaper to identify the bone’s owner as Nguyen Quang Hung, who lives in An Khe Town in the Central Highlands province of Gia Lai.

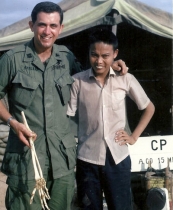

Sam Axelrad (L) with the arm bones of Nguyen Quang Hung (R) after the surgery. The American doctor plans to return the bones to the Vietnamese veteran soon.

“I am really surprised that Dr. Sam Axelrad still has my bones,” the 72-year-old father of seven said. “I hope that part of my body will be with me when I die.”

Axelrad, then 28, was commander of a medical unit attached to Camp Radcliff near An Khe when a helicopter brought Hung with a gangrenous arm and in critical condition.

“We immediately gave him antibiotics, checked his blood count, took him to surgery, and amputated his arm,” the doctor said. The right arm was amputated at the shoulder.

The doctor decided to keep the bones while nursing Hung back to health. The medics in the ward developed a special relationship with the young northerner, he said, but then his commanding officer found out about Hung.

“He gave me 24 hours to get rid of the ‘enemy,’” Axelrad said.

He flew by helicopter to Quy Nhon to get Hung’s release papers from the provincial governor and found a job at a clinic in the same city.

Tien Phong (Vanguard) newspaper quoted Hung as saying he was bored with the job and returned to Axelrad’s hospital in 1969 to work as a nurse’s assistant.

He contacted the local Viet Cong unit and was promised someone would come to pick him up. But he waited in vain.

Meanwhile, in August 1967 Axelrad returned home together with the bones, and did not hear about Hung until last week.

The injury

Hung, a native of the northern province of Nam Dinh, had been head of a northern Vietnamese advance squad when his unit was ambushed by American troops in Binh Dinh Province.

He sustained a gunshot to the right arm but escaped along a river. He survived “on rice left over in abandoned rice fields and wild leaves” for days before the Americans found and took him to Axelrad’s camp.

“I fainted when I reached the American medical site in An Khe. My arm had deteriorated and had such a bad smell.”

A month after the amputation, he said, Axelrad performed a second surgery on the remaining part of his right arm to save him from severe infection.

Upon his recovery, he was surprised to be sent to work in the clinic. “I thought they would send me to Con Dao prison after I healed but they did not.”

Six years after returning to An Khe, in 1975, he married a woman 14 years his junior.

After the war Hung worked for the Song An commune administration in An Khe for several years before becoming self-employed to feed his large family.

He now hopes to get war invalid status and the attendant allowances, which he never got, to help cover his sick wife’s medical expenses.

“It has been too complicated in terms of procedures to report the loss of my arm during the war.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, 74-year-old Axelrad is making plan to return to Vietnam with the bones.

“I have had his arm all these years as a reminder of a deed of kindness for a young man in need. But now it is not something I want to pass on to my grandson and it belongs to [Hung],” he said.

His son Chris Axelrad, an acupuncturist, herbalist, and nutritionist in the US, wrote on his blog that he had “never heard my father’s voice like that” when calling the military doctor to tell him about Hung being found.

“My father has thought about [Hung] over and over for the last 40 plus years,” the doctor, who was shown the arm bones the first time as a teenager, said.

“One of the hardest things for my father was leaving Vietnam and never knowing what happened to him.”

Upon his return from Vietnam, Axelrad continued to work as a military general surgeon. He was discharged from the army a year later and has been practicing urology since.

But a wife and three children and a successful career has not helped him get over the sad memories of Vietnam’s battlefields.

“Two years ago I opened my military trunk for the first time in 35 years… and the memories returned vividly,” he said.

He began to review the history of the war and read H.R. McMaster’s book Dereliction of Duty, which documented the lies told to Congress by President Lyndon Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

The American presence in Vietnam was a big mistake and a huge waste of life, he said.

“We should not have entered the war in Vietnam. This would have avoided the loss of 56,000 American soldiers and… 3 million Vietnamese.”

But the injuries caused to children and their separation from their parents bothered him the most.

His son said the doctor is “still very angry at Lyndon Johnson for all the lies he said.”

Now that he has learned about the one-armed Vietnamese veteran, Axelrad is looking forward to the day he will reunite with his old friend, honor his bravery, and make up in his own little way for the pain the Americans caused in Vietnam.

By Tran Quynh Hoa - Tran Hieu, Thanh Nien News